Vashti McCollum sits outside the Supreme Court building in 1947, while awaiting arguments before the court on her fight to ban religious education classes from an Illinois public school. Her case was one of the cases in which the Supreme Court began to interpret the First Amendment's religious establishment clause known as "separation of church and state." (AP Photo/Herbert K. White. Reprinted with permission of The Associated Press)

The first clause in the Bill of Rights states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

For approximately the first 150 years of the country’s existence, there was little debate over the meaning of this clause in the Constitution. As the citizenry became more diverse, however, challenges arose to existing laws and practices, and eventually, the Supreme Court was called upon to determine the meaning of the establishment clause.

Though not explicitly stated in the First Amendment, the clause is often interpreted to mean that the Constitution requires the separation of church and state.

Roger Williams, founder of Rhode Island, was the first public official to use this metaphor. He opined that an authentic Christian church would be possible only if there was “a wall or hedge of separation” between the “wilderness of the world” and “the garden of the church.” Williams believed that any government involvement in the church would corrupt the church.

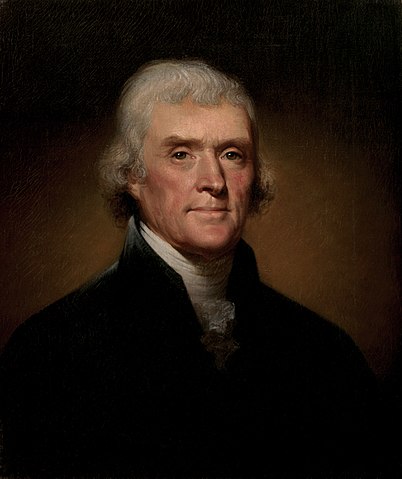

The most famous use of the metaphor was by Thomas Jefferson in his 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association. In it, Jefferson declared that when the American people adopted the establishment clause they built a “wall of separation between the church and state.”

Jefferson had earlier witnessed the turmoil of the American colonists as they struggled to combine governance with religious expression. Some colonies experimented with religious freedom while others strongly supported an established church.

Thomas Jefferson created the most famous use of the metaphor “separation of church and state” in a letter where he mentioned a “wall of separation.” (Image via White House Historical Association, painted by Rembrandt Peale in 1800, public domain)

One of the decisive battlegrounds for disestablishment was Jefferson’s colony of Virginia, where the Anglican Church had long been the established church.

Both Jefferson and fellow Virginian James Madison felt that state support for a particular religion or for any religion was improper. They argued that compelling citizens to support through taxation a faith they did not follow violated their natural right to religious liberty. The two were aided in their fight for disestablishment by the Baptists, Presbyterians, Quakers, and other “dissenting” faiths of Anglican Virginia.

During the debates surrounding both its writing and its ratification, many religious groups feared that the Constitution offered an insufficient guarantee of the civil and religious rights of citizens. To help win ratification, Madison proposed a bill of rights that would include religious liberty.

As presidents, though, both Jefferson and Madison could be accused of mixing religion and government. Madison issued proclamations of religious fasting and thanksgivings while Jefferson signed treaties that sent religious ministers to the Native Americans. And from its inception, the Supreme Court has opened each of its sessions with the cry “God save the United States and this honorable court.”

It was not until after World War II that the Court interpreted the meaning of the establishment clause.

In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Court held that the establishment clause is one of the liberties protected by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, making it applicable to state laws and local ordinances. Since then the Court has attempted to discern the precise nature of the separation of church and state.

In 1971 the Court considered the constitutionality of a Pennsylvania statute that provided financial support to nonpublic schools for teacher salaries, textbooks, and instructional materials for secular subjects and a Rhode Island statute that provided direct supplemental salary payments to teachers in nonpublic elementary schools.

The Schempp family, pictured here, brought suit that led to a 1963 ruling by the Supreme Court in Abington School District v. Schempp that banned bible reading and the recitation of The Lord’s Prayer in public schools, saying that it violated the First Amendment’s establishment clause requiring separation of church and state. (AP Photo/John F. Urwiller, used with permission from The Associated Press.)

In Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), the Court established a three-pronged test for laws dealing with religious establishment. To be constitutional a statute must have “a secular legislative purpose,” it must have principal effects that neither advance nor inhibit religion, and it must not foster “an excessive government entanglement with religion.”

The Court modified the Lemon test in Agostini v. Felton (1997) by combining the last two elements, leaving a “purpose” prong and a modified “effects” prong.

In County of Allegheny v. American Civil Liberties Union (1989), a group of justices led by Justice Anthony M. Kennedy in his dissent developed a coercion test: The government does not violate the establishment clause unless it provides direct aid to religion in a way that would tend to establish a state church or involve citizens in religion against their will.

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor proposed an endorsement test that asks whether a particular government action amounts to an endorsement of religion.

In Lynch v. Donnelly (1984), O’Connor noted that the establishment clause prohibits the government from making adherence to a religion relevant to a person’s standing in the political community. Her fundamental concern was whether government action conveyed a message to non-adherents that they are outsiders. The endorsement test is often invoked in religious display cases.

In McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union (2005), the Court ruled that the display of the Ten Commandments in two Kentucky courtrooms was unconstitutional but refused in the companion case, Van Orden v. Perry (2005), to require the removal of a long-standing monument to the Ten Commandments on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol.

David Harlow, left, and Michael Stys, view the Ten Commandments monument on display at the State Judicial Building in Alabama in 2002. A U.S. District Court ruled that placing the mounment in the state building was a violation of the separation of church and state. (AP Photo/Dave Martin. Used with permission from The Associated Press)

Questions involving appropriate use of government funds are increasingly subject to the neutrality test, which requires the government to treat religious groups the same as it would any other similarly situated group.

In a test of Ohio’s school voucher program, the Court held 5-4 in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002) that Ohio’s program is part of the state’s general, neutral undertaking to provide educational opportunities to children and does not violate the establishment clause. In his opinion for the majority, Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist wrote that the “Ohio program is entirely neutral with respect to religion.”

More recently, in 2022, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in Carson v. Makin that Maine could not exclude families who send their children to religious schools from its state-funded tuition reimbursement program. The program helped children who live in rural areas without public schools nearby, but said the tuition could not be used for religious schools. The court, in a ruling written by Justice John Roberts Jr., said that the policy violated the parents’ right to freely exercise their religion and that a public benefit that flowed to a religious school based on a parent’s choice did not “offend” the establishment clause of the First Amendment.

Most significantly in 2022, the Supreme Court marked a change in how it will interpret Establishment Clause cases going forward. In Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, the high court declared it had abandoned the Lemon test and instead, will interpret the Establishment Clause in “reference to historical practices and understandings.” In the majority opinion, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote that that the lower courts had created a “vise between the Establishment Clause on one side and the Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses on the other,” a conflict he associated with the Lemon test. Instead, he viewed the establishment and free exercise clauses as complementary and working together to decrease unnecessary government interference with religion.

From the colonial era to the present, religions and religious beliefs have played a significant role in the political life of the United States. Religion has been at the core of some of the best and worst movements in the country’s history. As religious diversity continues to grow, concerns about separation of church and state are likely to continue.

This article was originally published in 2009. J. Mark Alcorn is a high school and college history instructor in Minnesota. Hana M. Ryman is a Middle School Humanities Educator in Orlando, Florida.